Trip Blog

The saint of San Rafael

On the struggle out of the valley of San Marcos, a truck stopped and offered us a lift. It was driven by an Italian Catholic priest in traditional robes and two sisters with similar brown habits. They smiled so nicely as they told me about their lovely town of San Rafael and their special church. They encouraged me to visit San Rafael which I did the next day.

I took a bus out to San Rafael and did agree that is was a wonderful village. I got a private tour of Tepeac by the groundskeeper who had great love for this special place. According to an article published in the Nica News 21 (March 1999) “The most outstanding figure in the history of San Rafael is the Italian priest, Father Odorico D'Andrea. From his arrival in 1953 to his death in 1996, Father Odorico achieved virtual sainthood among the people of San Rafael and the surrounding communities. His image, a smiling, warm, obviously kind man in plain brown robes, can be seen in nearly every home, business and vehicle in the town. "It's so sad," said one community member, "that you weren't here to know him." Among his achievements are a formidable health clinic, a library, several neighborhoods for the poor, and the beautifying of the church.

The latter feat is truly impressive. Pastel-colored windows admit a calming light in which to view the many bright murals, bas-reliefs and shrines. Mention the padre's name to any local and you will immediately gain their friendship.

As time passes, the people of San Rafael speak even more greatly of Father Odorico. Many believe he performed miracles and that his body has not decomposed. You can check for yourself at his resting place, called the Tepeac and located on the hill overlooking the town. Ascending the stairs, you'll pass the Stations of the Cross to where the tomb it situated.“

I got to touch the tomb of this saint and see the seat he would rest in when he was tired and walk the quiet gardens he had also walked. I could see why the grounds keeper loved this place, it was a special place, I could feel the magic.

Guatemala South to Nicaragua Pictures

Here is a slideshow of the pictures from our re-start in Guatemala at the beginning of 2008 to the middle of Nicaragua. You can view all the pictures in full size and with their captions on flickr and see the show at flickr here. You can see all our photos at flickr.com/photos/hobobiker.

Agua Para La Vida: We're in Rio Blanco, Nicaragua

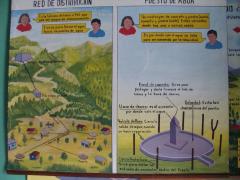

Last Tuesday we rode into Rio Blanco, in the rural, rural lowlands of Nicaragua, to visit an organization we'd been in contact with for a few years, so we'll be in Rio Blanco for a week or so. Agua Para La Vida (Spanish for "Water for Life") was founded 19 years ago toward the end of the dark war years when a CU Berkeley engineering professor came to this out-of-the way place for a visit with another charitable organization and found that there was no potable water at all in the village he was visiting. Being an engineer, he thought in terms of how to solve their problem with some water engineering, and he brought volunteers to the village over a period of a couple of years to put in a water system, complete with collection at the water source (a spring) and piping to distribution points. From that time to now APLV has grown into a modest but effective little organization, having completed more than 50 projects in the little villages mostly in the Rio Blanco area.

APLV has an integrated approach to water: They don't want to just deliver a water project, because without the other aspects of healthy living it doesn't do much, and won't be cared for properly anyway. They work with the community to make sure that each household member gets trained in a variety of health management techniques, including handwashing, proper storage and handling of drinking water, trash management, and the like. And each household gets an outhouse; normally in these villages there are very few outhouses, and you can imagine the health impact of having no sanitation facilities at all. Finally, APLV works with the community on reforestation of the area around the water source, for two reasons. The first reason is that it's important to get a tree-covered area around the source to prevent cattle or other animals from fouling it. But even more important is that the source will have a tendency to dry up in the future if proper vegetation is not maintained in the micro-watershed that feeds the spring.

We contacted APLV before heading this way and offered to help out where we could with computer issues, GPS management, and Autocad, and they put us right to work - it's quite a pleasure to see such a cadre of enthusiastic workers. Sometimes the workers in an organization like this can get a bit jaded or discouraged, working just as employees, but these people are all giving it their best, retaining their enthusiasm and commitment even after a decade or more on the job.

It's interesting to see too how humble an organization it is (in the good way). They've always maintained a commitment to making sure that every dollar goes to the project, to items of value, instead of to overhead. So their office is not with the other NGO offices on the main street, and definitely does not have a fancy storefront. It's just a nondescript warehouse-type facility on a back street (a dirt street, like most of the streets here) and has a simple sign.

Due to this same philosophy, APLV does not follow the signage practices of the other NGOs doing various projects here. (There are dozens of NGOs, or Non-Government Organizations, working here - you see them everywhere.) Most of the NGOs post a prominent sign after they complete a project, with an explanation of the project and the logos of all the NGO participants. We've seen these signs in little villages way out in the sticks ("100 outhouses, care of the European Union and World Vision", "Improved road, courtesy of the government of Japan", etc.) But APLV doesn't even put up a sign when the project is completed, for two reasons: First, because they want the dollars going to the project, not to a sign about APLV. Second, because the reality is that the water system and associated benefits are not just a gift. They are a cooperative venture in which the community has participated fully.

Donde estamos, Febrero de 2008: Nicaragua

Hola a todos nuestros amigos que hablan español. Disculpenos que no hemos escrito hace tanto.

Al principo del año empezamos de nuevo en nuestra aventura, después de recuperar de la tos ferina de Septiembre a Diciembre. Agarramos un vuelo a Guatemala, donde nos esperaban las bicicletas, bién descansadas, y empezamos a montar otra vez. Pasamos por otra parte de Guatemala, por los altos de Honduras y la capital Tegucigalpa, y ya estamos en Nicaragua.

Ya llevamos mas de 14,000 kilómetros y todavía no hemos alcanzado la mitad del viaje!

Pasamos la semana pasada como voluntarios con un organización muy interesante e importante. En este país tan pobre ellos ponen sistemas de agua potable en pueblitos rurales muy retirados. Así visitamos a un pueblito después de un viaje por caballo de mas de una hora para ver un sistema funcionando perfectamente, y la gente bien sana por razón de tener esa agua tan buena todos los dias. Ustedes pueden leer del trabajo de Agua para la Vida a este enlace.

Las fotos de esta parte del viaje están a aquí, y un mapa de nuestra ruta en Centroamérica esta a aquí. Las fotos de la visita con Agua Para La Vida están a aquí.

Les agradecemos a todos Ustedes por viajar con nosotros! Siempre nos dan tanto gusto sus correos electrónicos.

Gracias,

-Randy y Nancy

APLV: Home-Grown Leadership

Esteban Cantillano is one of the amazing success stories of APLV. In 1993 he was a campesino living in a little, remote village where APLV was developing a potable water project. He was elected the coordinator by the community, so was responsible for all the interface with the community. But he asked a pile of questions of the brigade from UC Berkeley that was putting in the system! He wanted to know about everything. He was eventually invited to join the first class of the "Potable Water Technical School", a technical high school program, but protested that he had only finished the 6th grade. They said "well, try it out - we'll take you on probation." That was in 1993. Needless to say, he finished with honors (and later went back and did his 7th-10th grade education!) and became one of the pillars of APLV. He has served in the technical/design role he was trained for, as the social coordinator (who does the contact with the village, local government, landowners, and the like), and is now in charge of the office here in Rio Blanco. He seems to know everybody, and to know everything about every project ever constructed by APLV.

Esteban is just one example of the depth of leadership that we've found here. All but one of the workers here is Nicaraguan, and they have a combined total of decades of experience with the organization. Many times an organization like this is directed from outside the country, and the workers are just salaried workers, doing the best they can, but for them it's a job. In this case we have local people who are fully invested in the past, present, and future of the organization. We're pretty optimistic about the future.

Agua para La Vida's in-country director is Carmen Gonzalez, who has been here for 3 years after 15 years with Habitat for Humanity, where she was involved with the building of hundreds of houses for needy Nicaraguans. In keeping with APLV's philosophy of putting money into projects rather than into comfortable surroundings and administrative costs, Carmen runs the national office out of her small house in Managua, with no administrative help, just her. She spends 2-3 weeks each month in Rio Blanco (four hours away by bus) living in the very modest home where we're staying right now (outhouse, running water and electricity but no hot water).

Her vision is to change APLV from an isolated organization dependent on aid from a few donors in the US and France into a robust, Nicaragua-centered NGO (the techie term for Non-Government Organization, or charity working in country). She's trying to establish new and sustainable funding sources and is trying to establish links with many other NGOs and to do joint projects, etc.

We certainly applaud this approach - when we were working with Friendship Bridge in Guatemala we went to one village where the women were all telling us that their young children were ill. They said that almost every child under age 2 was perpetually sick. But Friendship Bridge is a microfinance organization and at least the on-the-ground workers have no idea what health resources might be brought into play for this group. This seems to be a constant problem in Central America (and perhaps throughout the developing world) and so we certainly applaud the idea of building ways to solve problems which may be outside the purview of any particular organization.

Carmen also wants to make sure that APLV, while maintaining its efficiency and humility, can perform at the level of professionalism required by the various funding sources. They might be a great organization, but if they can't demonstrate that to a particular NGO funding source by showing that they execute in a professional manner, that fact could cut them out of the ability to do a number of projects.

Agua Para La Vida: The Community does all the work!

(We'll have pictures and updates to this article in a couple of days.)

When a community gets interested in a water project and approaches APLV, it has to go through a number of steps before the project can become a reality. One of the first steps is to commit to doing all of the unskilled labor and provide hospitality to the APLV technical staff when they are onsite. Although APLV provides the materials and engineering, the community does an extremely difficult job - each family normally commits to between 42 and 62 days of labor for the project. You can imagine what that means to people who have very little to take that much time out of the course of a project (6 months to a year). The families build their own outhouses, and the men do all the trenching and the concrete work. This is a pile of work, as the piping often runs for 6-9 miles (10-15 kilometers).

If you're interested in more information on Agua Para La Vida or would like to contribute, they have an excellent website at APLV.org where you can get the whole scoop or make a contribution. It takes just $30,000 to $60,000 to fund a complete village project that may benefit 100-200 families, complete with potable water, outhouses, community health training, and reforestation planning. It is even possible to fund an entire project (and then visit for the inauguration of the project), but of course most of us give in smaller chunks. If you have the means, we encourage you to talk with them about funding an entire project, since they have a couple for which the study, paperwork, and planning are already done and all that remains is to find the funding.

APLV: Reforestation and Environmental Work

The second day we were in Rio Blanco at APLV in Rio Blanco Fadir Rojas, APLV's reforestation engineer, took us for a hike up into the beautiful Cerro Musún wilderness reserve right next to the town, where he used to work as an engineer and ranger. We spent the afternoon climbing up into virgin forest to a beautiful waterfall called Cascada Las Golondrinas (the swallows). As we walked along we chatted about his responsibilities with APLV and the growing importance of reforestation within the goals of the organization.

Fadir is from a purely campesino family in the dry, heavily populated western part of the country. His parents barely went to school - perhaps to the first grade - and can't really read, but they pushed education in their family and Fadir is one of four university graduates in his family. He succeeded in getting full scholarships for his university education at the national university and is now, at 27, one of the elite young leaders of Nicaragua.

When Fadir came to APLV he found that their vision of reforestation was too limited: They understood the idea of using forest management to project the water source from contamination, but the integrated management plan did not include enough emphasis on protecting the watershed itself from deforestation. Of course any spring depends on the waters beng gathered by its watershed, and will dry up if all the trees are cut to provide pasture for cattle, or if all the upstream land is pressed into an inappropriate type of service.

So Fadir is trying to enhance the current protection model of reforestation with an additional watershed management model. He's a bright young man with a great grasp of what's going on and we think he'll succeed.

APLV: Promoting Health and Sanitation

The organization we visited in Rio Blanco, Nicaragua, Agua Para La Vida, believes in an integrated approach to making a difference in a community. So they don't just drop a potable water system and disappear. They try to set up a program that will be self-sustaining and which can make a long-term difference in the health and welfare of the community. For that reason they always provide an outhouse (actually constructed by the family), and have a health team in charge of evaluating the community's needs, training them in appropriate health practices, and monitoring the water quality of the installed system.

Lilian Bando and Gregoria Espinoza have been working for APLV in their role as health promoters for a dozen years, and they still find that their educational role is the most important thing they do.

When they arrive at a new project, it's quite common to find that there are few or no outhouses (of course there are no sewage or water systems, so outhouses, where they exist, are the workhouses of sanitation in rural Central America). And it's also common to find that the entire community is ignorant of basic concepts like handwashing after going to the bathroom, proper management of drinking water, appropriate disposal of trash, and the like. There are an awful lot of villages where defecating out back and letting the pigs and chickens clean up is normal, and that's not good on the health front.

Lilian and Gregoria have an entire health evaluation routine that they do at the beginning and at delivery of a project, and they they spend the bulk of their efforts doing group and family-by-family training on the critical aspects of health practices. By the end of their routine the practices and the health of the community can be much improved.

I was working with these two helping with a spreadsheet that analyzed the before and after health practices and statistics. According to these numbers, the instance of childhood diarrhea in the village we were analyzing dropped by 50-70%, which is a pretty amazingly good number. It's no surprise that the basic answers to "do you wash your hands after going to the bathroom and before eating" had improved amazingly as well.

Once again, it's a treat to see two women who have been working together on the same mission for more than a dozen years sticking to it with an impressive intensity and compassion. They only thing that really gets them down is when they work with a community that has so little to eat that it seems they need that before working on sanitation issues. Sometimes, they say, they just wish they could give out nail clippers to the families that can't even afford one.

APLV: The Potable Water Technical School

Agua Para La Vida is committed to truly sustainable solutions, and they have demonstrated it in the most significant way by actually starting a school for Potable Water Technicians.

The initial little tiny project that APLV did back in the 1980's, of course, was mostly done by brigades of volunteers coming down for a few weeks at a time. But when you do that, your project has little hope of being maintainable, because there is inadequate in-country expertise. To counter this, APLV started up the "Escuela Tecnica para Agua Potable", or Technical School for Potable Water back in the 1990's. It's a fully accredited 2+ year class involving every aspect of potable water design and development, including the theory and practice of planning and engineering the delivery systems and including everything else that APLV does with a project. Three classes have now graduated, and the fourth class (of 8 students) is about halfway through. For this class, 70 students from all over Nicaragua applied for the full-ride scholarship (including room, board, and tuition), and just the 8 slots were available. But what an education they get. They come out with all the mathematics and engineering to do technical work on water systems, and have a fully-accredited "Bachelor" degree, similar to an honors technical high school degree. Their presence in various organizations throughout Nicaragua means that projects don't have to spend money on high-priced consultants to do the work that these specialized technicians can do. APLV's "ETAP" school is the only school graduating water technicians in Nicaragua.

The school has typically been taught by workers who come from abroad to do a year or so of duty. The first group of students was taught by the founder of the organization on various trips to Nicaragua. This past year the curriculum has been taught by a talented French graduate engineer, Gilles Burkhart. Now that the school has matured, Gilles has a full building for the students, including men's and women's dormitory areas and a well-equipped classroom including computers.

Gilles is about to move to other duties within the organization, and he'll be replaced for the coming year by another French engineer. At the end of this two-to-three-year cycle, yet another class of qualified, trained potable water technicians will be available to APLV and to rural Nicaragua at large.

We crossed into Costa Rica today

The Island of Ometepe, our last hurrah in Nicaragua

After riding back south from Rio Blanco in Nicaragua we spent one night at the tourist town of Granada, the port town at the north of Nicaragua. It's all full of tourists from all over the world, an easy gringo destination with a nice climate and beach and lake and great gringo services. Made us a little crazy though. In the morning we got on the 3-times-per-week ferry out to the island of Ometepe, in the middle of the lake. It took four hours and we got in after dark, but the next morning we found a beautiful island with a pair of dramatic volcanoes. We spent 3 days exploring and waiting for the ferry that would take us all the way to the bottom of the lake where we crossed into Costa Rica. If you ever want an easy place to get away from it all and spend a week or so with a really easy lifestyle, Ometepe is the place. So laid back and beautiful. Cheap. Good tourist services. Lots of hikes and things, and you're in the middle of a huge lake so there's lots of beaches and beachfront hotels. A very nice place.

APLV: Visits to actual communities getting water projects

We visited three impressive communities getting drinkable water in the Rio Blanco area. One was just in the preparation and funding stages, one was partly done, and the third was complete and beautiful, with a very remote community having clean, healthy drinking water 24 hours per day. I'll start with the one that was finished and work back to the one that was just about to get started.

Okawas

We had the delight of visiting the community of Okawás for the official ribbon cutting and handover ceremony for the new system. We got in a truck at 5;30 in the morning and drove for a couple of hours to a river crossing beyond which there was no road, crossed the river in a long motorized canoe, and then got on mules for the hour-long ride to the village. The trail started out pretty easy, but turned into some pretty impressive muddy and rocky ups and downs. With our little experience with horses we were a little nervous about how they were going to navigate the difficult terrain, but they did better than we would have.

Once there, the whole team went into action. Gregoria and Lilian, the health promoters, began to visit each household to check on how all the health education was going and to see if the outhouses were working out, etc. Most of the rest took the time before the celebration to go up and inspect the entire system, including the tank, the water capture point (a sealed-over spring), and the piping. It all looked mighty good, as did the beautiful outhouses.

After that, the celebration began. Everything was decorated, with crepe paper around one of the community water spigots. Everybody gathered for speech-giving and celebration, including a local mariachi band (who had come up on horseback with their instruments). Thierry Sciari, the representative of the French organization Res Publica that funded this project, met all the members of the committee. There was the presentation of certificates to each family acknowledging their contribution and their completion of the health and water use training. We were even asked to help with the presentation of some of these things, and asked to give a little speech ourselves, I guess as representatives of other APLV donors!

All in all, it was a wonderful celebration of a more wonderful event. Nancy talked to one gentleman who had had health problems (parasites) for years and years and had never been able to shake them before the new potable water system went in. But now, with good water available all the time, he is free of parasites and healthier than he's been in his life.

La Enea: A water system just going in

I got to visit the very ambitious water project being at the village of La Enea, which involves capturing the water from a creek high on the other side of a significant valley, bringing it down across the river and then back up the other side of the valley to the village.

This is a tremendously ambitious project, the biggest Agua para la Vida has ever undertaken. It involves the capture of part of a stream instead of just a little spring (and might require chemical treatment) and involves something like 37 kilometers of piping, seven kilometers for the basic water delivery and the rest for the distribution system.

And the water system will be a tremendous boon to this community, because they currently have to haul their (poor quality) water from a stream four kilometers away. So most either walk with a heavy load of water or perhaps load a burro with a big load. Imagine the time it would take out of your day if you had to personally carry all the water you needed for drinking, cooking, and clothes washing from a source two and a half miles away.

My visit was with an entire team from APLV, and there was a major status meeting with the entire community. Most of the meeting was about making sure that the proper amount of community labor was organized, since the community provides all the unskilled labor, as much as 50 man-days of hard labor per family. In the current stage of the project most of the work is using a pick and shovel to dig meter-deep trenches for the piping through rocky, rocky soil.

We left the APLV skilled water technicians there when we returned, since they were going to spend the week working with the community laborers to make another push on the distribution line. These young people are so talented and impressive. They almost all come from campesino homes all over Nicaragua and have graduated from the Potable Water Technical School that APLV runs and are now directing and overseeing impressive engineering ventures. All of them would be staying the week in simple accomodations provided by the locals, some a bit more rustic that most of you would appreciate. But no complaining from this talented group.

Monte de Cristo

The third village we visited was Monte de Cristo, which is a candidate for a water system and which may get one this year. We rode in the back of a truck for an hour and a half or so to get around the huge mountain that rises up beside Rio Blanco, then crossed a river on foot and rode horses for an hour and a half to the village, which is completely inaccessible by vehicle. As novices on horseback, it seemed nearly inaccessible on horseback! The steep, muddy inclines and deep mudholes seemed to us like they'd be too difficult for the horses, but they took them slowly and carefully and got us there safely.

Monte de Cristo is a community partially formed by a catastrophe four years ago. A tropical storm stalled over the area, dropping an incredible amount of rain, eventually resulting in huge mudslides coming off of the Cerro Musun, the mountain that dominates the area. 40 people were killed, but villages were wiped out throughout the area, and Monte de Cristo was a resettlement village where the International Red Cross set up some services and some temporary housing (which is still in use, even though intended for only one season).

There were two major reasons for the visit: First, APLV normally conducts a number of community-training, health-training, and organizational and planning meetings, so all that was going on. But second, the village was being shown to Thierry, the representative of the French NGO "Res Publica", for possible sponsorship by that organization. We got to see how he approached the entire evaluation process, and how APLV does its various meetings and social organization up front.

Nancy will talk more about the visit to this remote village, but it was impressive to see the need, and to see how APLV handles the early stages of the process. We were exhausted when we returned that night!

Nicaragua Tidbits

We found Nicaragua to be a delightful country. Despite the fact that all any of us remember about it is the war in the 80s and the US involvement in it, Nicaragua is a tranquil, safe, and friendly place. We didn't have to pretend that we weren't Americans... We were received with great friendliness everywhere we went. We found no vestiges of the 1980's socialist agenda, and museums were the only obvious physical relics of the wars.

We had heard various things about safety in Nicaragua, but what we found was a country where nobody seems worried about crime at all (except in Managua, which we didn't visit). Nicaragua is reputedly the safest country in Central America, possi bly including Costa Rica in that tally. Sometimes in Guatemala and Honduras when we would ask about a particular back road we would be warned off: "not enough people there, not enough police, dangerous", in Nicaragua we'd ask and they'd say "oh, yeah, that's great, no problems with delinquency here".

All this and Nicaragua is the most resource-poor country in Latin America, with a per-capita average income for the whole country of just $700 or so. We saw some pretty simple shacks, and there are far more outhouses in rural Nicaragua than there are flush toilets. There may not be any flush toilets in rural Nicaragua. The more remote places may not have many outhouses, although many aid projects have been putting them in by the thousands.

There is an absolutely staggering number of NGOs (non-government aid organizations, or Non-governmental Organizations) working here. In remote villages on dirt roads we'd see signs: "1000 latrines provided by the European Untion", "Road improvement sponsored by Japan", "Environmental mitigation sponsored by World Vision". Every sign about a "project" would carry the logos of the various organizations that sponsored it. Despite all these active projects, there remains enormous need in Nicaragua. They're living on the raw edge economically. We saw projects sponsored by the aid organizations of governments: Japan, France, Spain, the US, and the European Union. And we saw some by religious aid organizations like World Vision and Save the Children. And there were a few little independents like Agua para la Vida that we visited in Rio Blanco, and a significant house-building and community improvement project run by a Rotary Club out of California.

There aren't many people here who speak English, but English is a prestige language, so there are lots and lots of businesses that carry mangled English-type names like "Bar Jonhy's" or an eatery called "Lucy's Delihgt".

Prices in Nicaragua were among the cheapest we've found. We spent $5 to $20 for a hotel, about $30 for a doctor visit, full lab tests,` and 4 kinds of antibiotics and other drugs, $1.50 -$2.50 for a simple meal in a comedor or $3-6 for a meal in a restaurant.

Nicaragua has a real up-and-coming and very unique tourism program. In addition to major development on the Pacific beaches and the classic gringo hangouts in Granada and Leon, there is the delightful, quiet island of Ometepe in the middle of Lake Nicaragua (good tourist services, quiet, plenty of things to do, cheap). But the most fascinating thing they have is called "rural ecotourism". There is a whole book published and available throughout the country on little tiny tourism opportunities where you can visit a poor rural family, spend the night, hike or horseback ride in a nature reserve or get a glimpse of their daily work life, all for $5-$20/day. The directory of opportunities is in Spanish, but would be accessible via any of the many tourist travel agencies in Nicaragua.

Nicaragua probably was a little harder on us health-wise than other places we've been, but we don't know why, of course. Both of us had intestinal issues, and both had a fever to go with it for the first time on the trip. But we were way off the beaten track and found great healthcare to help us out.

Nicaragua: Highly recommended!

Costa Rica: Just a quick visit

One of the delights of bike touring is that you spend most of your time in between big important tourism centers, instead of just going from one gringo hotspot to another. We get to meet ordinary people who are fascinated with us and have lots of questions and freely share their time and enthusiasm with us. And they are ordinary people who have not gotten jaded or tired of gringos or tourists. This is how the vast majority of our time in Mexico and Central America has been.

Then comes the famous tourist mecca of Costa Rica. Even though we've been here before, we didn't realize that the entire country has transformed itself into one huge vacation resort, almost an eco-Disneyland. We hardly passed a mile-long stretch in the whole country that didn't have tourist facilities and a sign in English. And we weren't in the main tourist part of the country! We probably didn't stay anyplace where there wasn't somebody that spoke English. Costa Rica is doing a fantastic job catering to tourists from all over the world, including all over Europe, the US and Canada, the Far East, and even places like Argentina. And there are no armed guards at the banks, which is a good sign. And it seems every town has a beautiful bakery where you can get fresh baked goods early in the morning.

This is all great news for the ordinary tourist: great services, easy living, great eco-tourist opportunities in rainforests and beaches. But it came as a bit of a shock to us after so much time being treated as rock stars by all the delightful people of rural Central America. Suddenly we were just ordinary gringos, like the people there every day, an economic force in the country, not a crazy curiosity. Instead of calling out "Gringo!" as we passed, people didn't even look at us, and might not even say hello when we greeted them in passing. It was quite a shock. An understandable one, but a shock nonetheless.

The economy and standard of living here are far above what we've seen elsewhere. Although we saw a few obviously poorer houses in Costa Rica, they generally had TV antennas, meaning that they had electricity (and we'd bet on running water, a luxury in many parts of Central America). Where we would see two or three tire-flat repair shacks in an ordinary town in Nicaragua, in Costa Rica, in one small town, we saw two car decoration and upgrade businesses, advertising all kinds of add-ons to your vehicle, including paint jobs, alarms, and the like.

All through Central America the vast majority of the buses have been old retired schoolbuses from the US, many still sporting the name of the school district where they used to haul school children. In Costa Rica they have big, beautiful, shiny buses like the great buses of Mexico.

The roads of Costa Rica were not as good for cycling as we had followed in the rest of Central America, even though we had planned carefully to avoid the terrible congestion of the Central Valley and the Pan American highway. Most of our route was OK, and some was delightful, but a fair bit had too many cars, trucks, and buses for the narrow, narrow roads. And then we hit the main east-west highway, and it was intolerable for cycling. We got on a bus for the 80 kilometers to Puerto Viejo. You could probably ride it, but you would give up bike touring if you rode much of this kind of road.

We did have a delightful stay in Cahuita, a little beach town on the Caribbean coast, enjoying the easy hospitality of the Caribbean blacks in the neighborhood. The national park there was delightful, but the coral reef has been devastated by a number of the negative forces working on reefs everywhere, but mostly by snorkelers breaking the coral.

One odd note where Costa Rica is behind: It has long had a pretty strong central government, and many things that are deregulated in other countries have not been deregulated here. You can buy a new cellphone and get immediate prepaid service in any little town in Central America. But not in Costa Rica. The government telecommunications monopoly is still the only game in town, so you have to sign up for a telephone line, wait for one to become available, and sign a contract.

Other good things: No guards with submachine guns at the bank. There's a fancy bakery in almost every town that opens at 5am. And the water is drinkable almost everywhere.

But we were happy to be the center of attention less than two miles into Panama, when the kids started calling out to us again!

Into Panama - We're already in Panama City

We got to Panama from Costa Rica about ten days ago and have been working our way the (fairly long) length of the country.

We crossed an old railroad bridge to get across the border from Costa Rica on the little-used border crossing on the Caribbean - once again, no problems and no hassles, although we had to wait an hour or so for the single Panamanian clerk to get back from lunch or something.

From the border we rode another couple of hours to get to the pier for the water taxi to the main island of Bocas del Toro, a fantastic touristy area with lots of snorkelling and completely overrun with tourists. We had a very pleasant day snorkeling, seeing the brightest and most beautiful coral we've ever seen. Then we got back on a water taxi, went to the mainland, and started the ride through Panama.

In northern Panama we saw some amazing living situations - lots of shacks on the water, or in other areas on stilts. We rode through indigenous areas with people in more traditional clothes.

The second day out, we had the honor of doing our biggest one-day climb of the entire trip, over 6000 feet (almost 2000 meters). We crossed over the Continental Divide, hitting a maximum elevation of 4200 feet, and then descending the whole thing. The Caribbean side was mostly virgin rainforest, with waterfalls. Besides being quite a grind to get up, it was beautiful and exhillarating.

After we got over the top, we hit the Pan-American highway and had a few days of good-quality riding on a mostly excellent road through very rural areas. Then, when we hit Santiago, it started gradually turning into American suburbs - big box stores and eventually McDonald's in every town, with the increase in traffic you'd expect. But much of this was on a 4-lane highway with a shoulder most of the time, so it was fairly safe.

We rode into Panama City today, over the famous Bridge of the Americas. Riding up to the bridge, we were stopped by the police and informed that cyclists are not allowed on the bridge, and that we'd have to wait for a patrolman to take us over. But the patrolman came with too small a vehicle, so he escorted us over the bridge and we had a wonderful crossing, with a careful flashing-light police escort!

(Our monthly email) Trip Update

We arrived in Panama City about 10 days ago and are taking a break now before going on to South America. Nancy flew to California for three weeks to help out her dad, who has been ill. He's much better now, but her help at home is much appreciated. She'll be back in early April and we're planning to take a boat to Cartagena, Colombia to begin the South American chapter of our trip. (What, you say? "I thought you weren't going to Colombia?" Well, what we hear from everybody we've met and even from the US State Department is that Colombia has improved markedly in the last few years and is an absolutely wonderful place to visit. So we'll keep our eyes and ears open and go that way.)

We have pictures for you: Costa Rica and Panama pictures and Nicaragua Pictures

And the map of our Central America route is complete so you can see exactly where we went.

And of course, there are lots of stories of our travels on the website: www.hobobiker.com. And we added lots of articles about the amazing organization we visited in Nicaragua, Agua Para La Vida. You can read about the incredible job they're doing providing sfe, clean drinking water to very rural villages in Nicaragua at www.hobobiker.com/aplv.

Leaving Rio Blanco, Nicaragua, we rode toward the famous and historical tourist center, Granada, and then took the ferry to the volcanic island of Ometepe, a wonderful place to spend a few days. Then we took the ferry from there to the bottom of Lake Nicaragua and went across the border to Costa Rica, where we started riding in earnest. We rode to Cahuita, a delightful hamlet on the Caribbean side of the country, before taking any tourist time, and then we proceeded right into Panama along a little-used route on the Caribbean side. We had a little more good tourist time in Bocas del Toro where we snorkeled and saw the most beautiful coral we've seen anywhere, and then rode over the Continental Divide in our biggest one-day climb of the entire trip. Finally, we rode several days down the Pan-American highway, emerging from rural Central America into significant cities with big-box stores and finally riding (with a police escort) over the Bridge of the Americas into the amazingly cosmopolitan Panama City, where skyscraper condos are everywhere and there seems to be money beyond anything we've seen since we crossed into Mexico. (Panama City looks more like Miami than anyplace we've been in Central America. It looks set to replace Miami as a hub for all of Latin America.)

Anyway, we have lots of hopes and fears for the next part of the trip. We hope to cross all the way down the Andes in the next year to arrive at Ushuaia, the southernmost city in the world, about this time next year, March of 2009. Our fears are not of bandits and terrorists, but of the big mountains and high elevations that we'll have to work with in the Andes. But shoot, we've made it this far...

One final thing: We were so inspired with our visit to Agua para la Vida that we're going to start mentioning this worthy organization in our notes and on the website. We encourage you to consider sending them a donation of any size from $10 to enough to fund an entire water project for a remote rural village (only $30,000 or so!). Learn more, including how to give, at aplv.org.

Anyway, thanks so much for riding along with us! We sure do appreciate you coming along "virtually". Drop us a note when you think of us!

-Randy and Nancy

Immigration Paperwork

Well, today I had my first taste of official paperwork and such. To date, passing all those borders, we haven't had any issues or problems at all. None of those horror stories you hear about crossing borders in Central America. No bribes, no corruption, no paperwork. We had to wait an hour for the border official to come back from lunch in Panama. Not too bad.

But in Panama they (seem to) only give you 30 days in the country. It's marked very clearly on our paperwork. So since I'll be here a tad more than 30 days (with Nancy home helping her dad) I went down to the immigration office today to do the deed. I figured it would take a little time.

First I waited in a long line to get a number and they took my passport number and told me I had to go across the street and get copies of my passport, the entry stamp, and the tourist card, along with 2 photos of myself.

I went and got the copies and the pictures from the very busy little stand across the street.

Then I went back and looked at the "next serving" sign, seeing that it would be a couple of hours at least before mine came up. So I started asking around what I needed to do. They told me that I couldn't apply for the extension until I did the registration, and that I'd have to get and fill out forms for both registration and the extension. So I went and stood in the line for the copier, which is where you get the forms.

Then I went back across the street to buy a pen, and filled out the forms.

Then I went back in and started asking everybody who looked competent what I should do. They told me to go to one line. While waiting there I asked somebody else who looked competent. He said to go to the other side of the room and wait in that line. While waiting in that line I asked the only actual available person who actually worked for the migration department, and he informed me that the law has changed and I can legally be in the country 90 days regardless of what the paperwork says. And he pointed to a little sign above the window that did seem to confirm this.

So I folded up all my paperwork and left. I hope I understood correctly!

Saludos de Panamá

Un peresozo y su bebé en

Costa Rica

Ya alcanzamos mas o menos la mitad del viaje. Hemos viajado en bici casi 16,000 kilómetros desde el inicio del viaje en Inuvik, Canada el 9 de Junio de 2006.

Llegamos en la capital de Panamá hace dos semanas y ya estamos descansando antes de continuar en America del Sur. O sea, Randy está descansandose. Nancy regresó por avión al estado de California, en los Estados Unidos, apra ayudar a su papá, quién ha estado enfermo (y que ya está mejorando). Ella está ayudando con toda su cuida ya que ha regressado a la casa del hermano de Nancy.

Nancy regresa en los principios de Abril y intentamos ir por bote a Cartagena, Colmbia, para empezar la parte de Suramérica. Originalmente no habíamos planeado visitar a Colombia por razón de la supesta inseguridad, pero hemos oido de muchos viajeros y otros fuentes que la situación ha mejorado bastate y que el país es maravilloso para visitantes. Claro vamos a tener cuidado.

Hay nuevas fotos para ustedes: fotos de Costa Rica y Panama and las de Nicaragua

Y el mapa de nuestra jornada en America Central está completo para que puedes ver nuestra ruta exacta.

También hay muchas historias en Hobobiker: www.hobobiker.com. Claro que los demás son en inglés, pero hay malas traducciones aquí. Hay historias (también mal traducidas) de la organización Nicaragüense Agua Para La Via aquí.

Después de salir de Rio Blanco, Nicaragua (donde visitamos y fuimos voluntarios para Agua para la Vida) pasamos al centro turístico Granada, y de allí fuimos por barco a la isla de Ometepe, un lugar precioso para pasar algunos dias turísticas. De allí fuimos por barco al fondo del Lago de Nicaragua y cruzamos la frontera de Costa Rica, donde empezamos a montar con mas fuerza. Llegas después de unos dias a Cahuita, una aldea al lado del caribe del país antes de descansar, y entonces continuamos cruzando la frontera de Panamá. Allí en Bocas del Toro tuvimos la oportunidad de hacer snorkel y vimos corales de colores tan brillantes que nunca habíamos visto antes. Después cruzamos las montañas a la carreterra panamericana (al lado del Pacífico) y pasamos varios dias yendo a la capital de Panamá. El paisaje se cambió de un mundo rural y centroamericano an mundo urbano, con grandes almacenes y anuncios al lado de la carreterra. Por fin cruzamos (con ayuda de una patrulla de policia!) el Puente de las Americas que cruza el canal de Panamá y llegamos a la ciudad, que es grandísimo y moderno, con grandes skyscrapers de acero y vidrio en todas partes, como la ciudad de Miami en Florida en los Estados Unidos. De hecho parece que Panamá podría competir con Miami como un centro comercial y de negocios para toda América Latina.

Tenemos muchas esperanzas y miedos para la parte próxima del viaje. Esperamos pasar todo la región de los Andes de sudamérica en el año que viene, llegando en Ushuaia, Argentina (en Tierra del Fuego, la Patagonia) en Marzo de 2009. Nuestros temores no son de ladrones ni de la delincuencia, pero de las montañas grandes y altitudes increibles que vamos a encontrar en los Andes. Pero llegamos hasta aquí...

ve to work with in the Andes. But shoot, we've made it this far...

Una cosa mas: Nuestra visita a Agua para la Vida en Nicaragua fue tan impresionante que vamos a mencionar esta organización en nuestros correos y en el website. Tal vez ustedes pueden considerar un poco de ayuda a Agua para la Vida para que puedan proveer mas agua potable para las aldeas remotas de Nicaragua. Una donación de cualquier tamaño ayuda mucho. Usted puede aprender mas, inclusive como donar, en aplv.org (vee la sección en español).

Pués, muchas gracias por acompañarnos. Mandanos en email cuando piensas en nosotros, y les damos nuestos saludos desde Panamá!

Gracias,

-Randy and Nancy

Nancy's tips on riding the roads of Latin America

I wrote this in response to a letter of consternation from one of the few other women (and one of the very few other "mature" couples) riding a route like ours in Latin America. It seemed worth while sharing with you, my management technics on how I managed riding the roads of Latin America.

This intrepid rider sent a note saying that the roads of Mexico were freaking her out so she was hopping on buses to avoid certain stretches and was having a difference of opinion about the risk level of the roads with her husband. Here is my response, such as it is:

First of all, I do think you have great amount of courage and smarts and capabilities. I admire you on many accounts. Anyone that has ridden Copper Canyon the way you you did has my admiration. If I knew you better, I might be more comfortable telling you that you have balls.

In retrospect, after riding through Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama, my thoughts about riding in Mexico are that it is a difficult country to ride in, especially as you get closer to the cities. The bigger the city, the more aggressive the drivers, and less room for mistakes. That said, indeed, in order to keep yourself safe, one person in the group always has to be the most reasonable (usually the woman) to do what it takes to keep going safely and in one piece, both physically and mentally.

Here are some of my/our ways we keep going, keeping in mind I have more fear than Randy (or is it more sense?).

- I always use a helmet mirror, I can see 180 degrees behind me. It took me about ten days to get used to it. A few years latter I got Randy converted. At first we both used used a handlebar mirror but it is not good enough. With a helmet mirror or a mirror on the glasses, I can turn my head just a little bit and see completely in back of me. This is the number one thing that keeps me safe. Randy now rides 1000 times safer. He had many close calls that he was unaware of and therefore unable to take defensive action. So, you ask, what does it do for me? I can get off the road when there is just not enough room for all the traffic or I can take the whole lane when there is not enough room for the vehicle in back of me to pass or I can hear another vehicle is coming around a corner that the driver in back does not know about. I also walk sections that just do not make sense to ride, like blind corners up a steep mountain. Sometime I ride on the opposite side of the road where there is a better shoulder or no gutter. Mexico gutters suck. The roads in Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua do not have those steep gutter drop offs.

- A rule we try to follow with one or two exceptions, is the weakest link (usually me) gets to make the call. If one of has a concern we stop and discuss it and find a solution. One solution is to find a secondary road. We used a map of Mexico called Guia Roji which had yellow roads shown as secondary roads, we tried to ride mostly those. The ones with pavement but without painted lines were a great joy because of the light traffic and they brought us to places way out of the way which added increased interest for us. We always asked locals if there was alternative roads to get to where we wanted that where quite with less traffic. Most locals knew a different route. Also we use a GPS in many roads where on there but we relied on asking the locals.

- Another technique is when one of us gets freaked out by the traffic conditions or whatever, is to stop and regroup. During the rest we decide the best course of action, whether it is to find another route, just rest and regroup, use a different technique, or even take a bus. (We did take a bus because of traffic on one road in Costa Rica seemed deadly to me, but that's the only time we've actually done that. Not the only time we've taken a bus, but the first time we were forced off the road and into a bus by our perception of the highway and the traffic. That road from San Jose to Limón is just not for bikes. A few days after we attempted to ride it and bailed by hopping on to a bus, someone referred to it as the road of death)

- We do not separate -- except once when I was sick, I bused to the next town and got a hotel about 15 miles away. We stick together even though it means that one of us (Randy) probably won't get as far in a day, and both of us are affected by the other's riding style, of course. Randy rode many thousand of miles alone before we started this trip and he hated it. He was lonely and miserable. A key for us is to stay together and get to a safer place. Even though Randy hates to get rides and I respect that, we have a handful of times gotten rides when it just made more sense for various reasons. He use to be purist but he benefits more for taking an occasional ride. We stay together. One time we took a bus in Mexico was from Durango to Zacatecas - the vacation period of Semana Santa (Holy Week) was just coming up and it was reputed to be quite dangerous just as we were approaching a long (and probably quite boring) stretch of road.

- We wear real bright clothes when traffic is heavy. You know that green that screams I am really a yellow.

- When the traffic is intense, I feel better when Randy rides in back to give me a buffer, but not too close, so I can still see traffic in my mirror and I can take evasive action when required but not endanger him by my action. The one in back is given less room by the traffic then the one if front. By the time they pass me they have pulled into the other lane. Randy does not freak out but being the one in back as much as I do.

- As far as taking a bus ahead by yourself and letting your riding partner ride and catch up with you at the end of the day, You have to go by your gut. Every woman feels differently. For me, I found I have felt perfectly safe. I am 53 and not such a target as if I was much younger female. I do my business in the day and I do not go to big cities alone. If I feel strange vibrations, I usually go introduce myself by name and ask their name. It is the ones you do not see that our the problem. I ask for help if I need it and everyone is glad to help out and it give you a new adventure in making contact with the locals.

- One last thing - we have an agreement that any way that either of us wants to cope with the traffic or road safety is OK. In other words, there are no recriminations about "why did you get off the road - there was no problem" or "why are you afraid?" Each of us has a different experience at every moment, and we both have different fear and perception levels.

Do what you can to keep going. Take a break in a nice place for a period of time and them start again.

I hope I do not sound like I have all the answers because I do not. Every road is different. The Guatemala border crossing freaked me out because of the new experience of all the chicken buses coming up behind us. Boy are they aggressive but mostly with the loud horns. I thought they where saying "Watch out I am coming through and if you are in my way I am going to get you." But after a few days I found they really said, that they where coming though, yes, to give you warning but mostly to let the people know that their rides are coming or around corner to warn others of their presence and other times just to say hi, great job. They are very expressive with those horns. But they are good drivers and used to avoiding all sorts of things on the road, including cyclists. They don't get paid for having accidents or killing cyclists. I find that if everyone cooperates, including us, we all get along just great

Ok, I think I answered you question. Thanks for giving me a chance to run on at the mouth. You can tell we've talked and thought a lot about this. But our experience has been quite good.

Randy also wrote some notes on riding in Mexico, safety, maps, and route selection

test entry - delete this

One of the delights of bike touring is that you spend most of your time in between big important tourism centers, instead of just going from one gringo hotspot to another. We get to meet ordinary people who are fascinated with us and have lots of questions and freely share their time and enthusiasm with us. And they are ordinary people who have not gotten jaded or tired of gringos or tourists. This is how the vast majority of our time in Mexico and Central America has been.